The Fight for Women’s Voting Rights

The women’s suffrage movement was a long struggle to win the right to vote for women in the United States. It took nearly 100 years for activists to reach this goal. It wasn’t easy because people disagreed on how to move forward. But on August 18, 1920, the 19th Amendment was finally approved, giving women the right to vote. For the first time, women were given equal voting rights as men.

The Early Years: Before the Civil War

The fight for women’s voting rights began before the Civil War. In the 1820s and 1830s, most states allowed all white men to vote, no matter how much money they had. During the same time, reform groups—such as those against alcohol (temperance movements), religious groups, and anti-slavery organizations—became popular. Many women were leaders in these groups and began questioning the idea that their only role was to be obedient wives and mothers.

The Seneca Falls Convention

A key event in the fight for women’s rights happened in 1848 when reformers like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott organized the Seneca Falls Convention in New York. At this meeting, they talked about the rights women should have. They agreed that women should have their own political identities and should have the same rights as men, including the right to vote. The convention wrote the Declaration of Sentiments, which stated that “all men and women are created equal.”

The Civil War Slows Progress

In the 1850s, the women’s rights movement was growing, but it slowed down when the Civil War began in 1861. After the war, two important amendments changed the discussion about voting rights. The 14th Amendment, passed in 1868, said that all citizens were protected by the Constitution, but it described citizens as male. The 15th Amendment, passed in 1870, gave Black men the right to vote but didn’t include women.

Disagreements Among Suffragists

Some suffragists (people who fought for the right to vote) believed that they should fight for voting rights for everyone—men and women. They were upset that the 15th Amendment didn’t include women. They even joined forces with some white Southerners who wanted to use white women’s votes to outnumber Black voters. Other suffragists thought it was more important to focus on getting Black men the right to vote first, so they supported the 15th Amendment.

Two Groups Work for Change

In 1869, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony started the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), which worked to get a national law passed that would give women the right to vote. At the same time, another group, the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), focused on winning voting rights for women state by state. In 1890, the two groups merged into one: the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). They argued that women should vote because they could help improve society by bringing positive moral values to politics.

Winning Support Across the U.S.

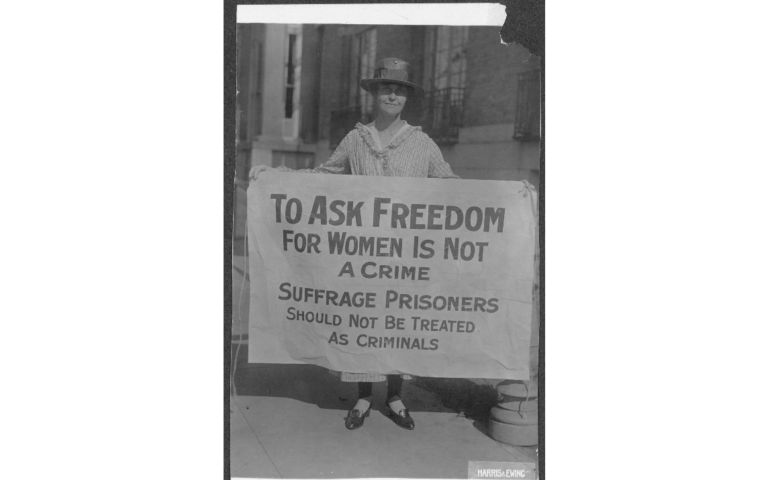

By the early 1900s, many states in the West had already given women the right to vote. However, southern and eastern states were slower to make changes. In 1916, NAWSA leader Carrie Chapman Catt came up with the “Winning Plan” to target these areas and fight for voting rights nationwide. At the same time, the National Woman’s Party (NWP), led by Alice Paul, used more aggressive methods, such as hunger strikes and protests, to push for their cause.

World War I and Final Victory

The movement slowed down again during World War I (1914–1918), but women’s work during the war strengthened their argument. Women showed they were just as dedicated to the country as men and deserved full citizenship, including the right to vote. Finally, on August 18, 1920, the 19th Amendment was ratified, giving women the right to vote. In November 1920, over 8 million women voted for the first time in U.S. elections.